From the early days of Christianity, believers have been called to engage with the world while remaining spiritually distinct (John 17:13-16). This distinction is characterized by a commitment to ethical living and personal conduct. In the mid-second century, as Christian values began to wane, a group of dedicated Christians—both men and women—responded by embracing a more austere lifestyle, marked by chastity, celibacy, poverty, prayer, and fasting (as noted in the writings of Justin, Athenagoras, and Galenus).

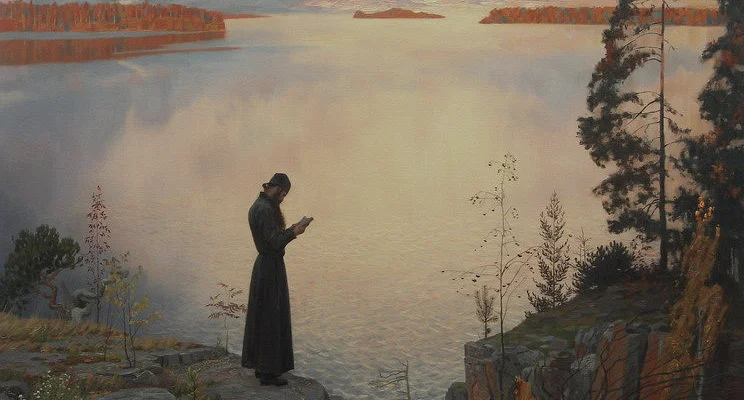

These early ascetics aspired to live a life akin to that of angels (Matthew 22:30), often choosing to live in solitude or forming small communities. By the third century, many of these Christians fled into the deserts, where they established permanent dwellings. They became known as “anchorites” (from anachoresis, meaning departure), “hermits” (from eremos, meaning desert), and “monastics” (from monos, meaning alone, signifying a life lived in the presence of God).

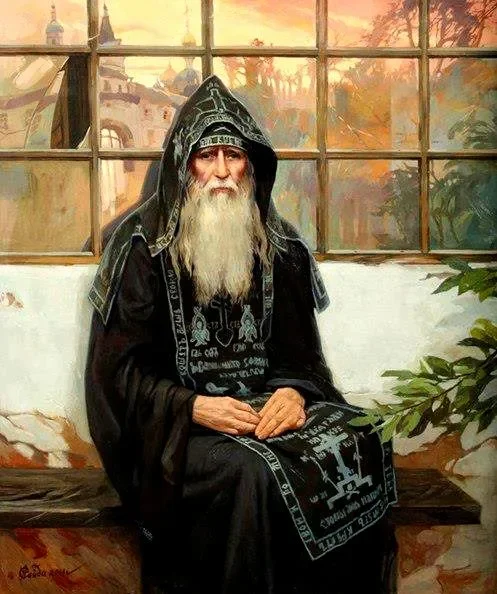

A prominent figure in this tradition is Saint Anthony the Great, who retreated to the Egyptian desert around 285 AD. His example inspired many others to follow, effectively “populating the desert.” These monks often lived in small huts, forming communities known as “lavras.” Saint Anthony is revered as the Father of Orthodox Monk, embodying the ideal of solitude with God, which has continued to inspire Eastern Orthodox monks throughout history.

The legalization of Christianity by Constantine the Great through the Edict of Milan in 313 AD coincided with a decline in the ethical standards of many Christians. In response, a new wave of monastics arose, seeking to distance themselves from worldly compromises. Monastic life flourished, particularly in Egypt, with significant centers emerging in the Nitria desert, founded by Abba Ammoun, and in the desert of Skete, established by Saint Makarios of Egypt. These monks adhered to the ascetic principles laid down by Saint Anthony, living in isolation and gathering for communal worship only on weekends.

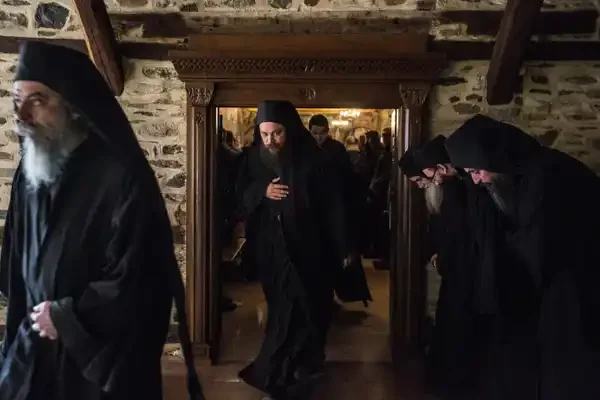

While Saint Anthony is recognized as the pioneer of anchorite monasticism, Saint Pachomios of Egypt (d. 346) is credited with founding cenobitic monasticism, which emphasized communal living. Starting as an anchorite in the Thebaid, Pachomios established the first true monastery, where monks lived together, shared resources, and participated in common worship and work. This new form of monastic life included a distinctive habit consisting of a linen robe, a goat or sheep skin coat, and a cone-shaped head covering.

During this period, monks were viewed as laypeople striving for Christian perfection, without the requirement of religious ceremonies or vows. They were also barred from clerical roles.

While anchorite monasticism existed beyond Egypt, cenobitic practices spread to regions such as Sinai, Palestine, and Syria, largely due to the influence of Egyptian monks like Saint Ilarion and Saint Epiphanios. Monasticism became closely associated with the more charismatic elements of the early church, leading to some controversial practices. Notably, the teachings of Eustathios of Sebastia, who advocated for extreme asceticism, sparked concern and were ultimately condemned at the Council of Gangra (343 AD).

Another heretical movement known as “Messalianism” emerged around 350 AD in Mesopotamia. Followers rejected the sacramental life of the church and claimed to experience direct visions of God. This group was eventually denounced by the Third Ecumenical Council of Ephesus in 431 AD.

In Constantinople, the influence of Messalian practices led to the development of the Vigilant (Akoimetoi) monasticism in the mid-fifth century, with the Studion monastery gaining prominence for its opposition to Iconoclasm. Saint Symeon of Antioch also pioneered the Stylite form of monasticism, famously living atop a pole for over 36 years.

As monasticism grew in significance within the church, the church began to guide this movement, ensuring it aligned with broader ecclesiastical needs. One major development was the formal ordination of monks, who took special vows, establishing a unique class of Christians that stood between clergy and laity. This evolution was largely facilitated by Saint Basil, Archbishop of Caesarea in Cappadocia.

Through these historical developments, the Orthodox monk emerged as a vital figure in the spiritual landscape of Christianity, embodying the call to a life of prayer, solitude, and communal living.

Basil the Great and the Foundations of Orthodox Monk

Eustathios of Sebastia played a pivotal role in introducing monasticism to Asia Minor, significantly influencing Saint Basil the Great. Basil adopted several beneficial elements from Eustathios’s innovations, including monastic garments, the establishment of monastic vows, and the special religious service known as tonsure, which designated monks as a distinct class, superior to laypeople yet subordinate to the clergy.

Among Saint Basil’s many ascetic writings, two are particularly crucial for regulating monastic life: the “Great Rules” (Oroi Kata Platos) and the “Brief Rules” (Oroi Kat’ Epitomen). These texts define the structure of life in cenobitic monasteries, emphasizing communal living as the ideal expression of Christian life—the “life of perfection.” They also caution against the perils of solitary anchoritic existence. Basil’s Rules became foundational for monasticism in both the East and West, serving as a kind of Magna Carta. In the Eastern Orthodox tradition, the anchorite spirit of Saint Anthony has persisted as the original monastic ideal, sometimes challenging the organized cenobitic structure introduced by Saint Basil. Conversely, the Western Christian tradition, particularly after adaptations by Saint Benedict, maintained a commitment to this organized monastic spirit.

Saint Basil envisioned Christian perfection as the ultimate goal of monastic life. Monks were expected to practice virtues collectively, especially love, obedience to their spiritual father, chastity, and poverty, while sharing communal resources. Once they achieved a level of Christian perfection, monks could return to society to assist others in their spiritual journeys. This approach positioned monks as “social workers,” actively contributing to the church’s mission in the world. Basil’s initiatives, such as the Basileias—serving as an orphanage, a kitchen for the needy, and a school for the illiterate—were effectively run by monks, showcasing his intent to leverage the monastic movement for the church’s outreach.

Following Saint Basil’s model, the Fourth Ecumenical Council of Chalcedon in 451 AD reinforced the structure of monasticism within the church. The council decreed that all monastics within a diocese would be under the direct authority of the diocesan bishop, who alone had the power to approve the establishment of new monasteries (Canons 4 and 8). This regulation effectively prevented the formation of monastic “Orders” as seen in the Western tradition during the Middle Ages.

Monasticism also spread to the West, with roots tracing back to Saint Athanasios of Alexandria, who was exiled to the West in 399 AD. His work, the Life of St. Anthony, was translated into Latin by Evagrios of Antioch around 380 AD. Latin monks like Rufinus and Saint Jerome, who lived in Palestine, were instrumental in bringing monasticism back to the West in the latter part of the fourth century. Saint Ambrose of Milan (d. 395) Northern Italy was first exposed to monastery customs around 395, and Saint Augustine (d. (d. 430) helped establish them in Northern Africa, eventually influencing Spain. In Northern France (Gaul), Saint Martin of Tours (d. 370) and in the South, Saint Honoratus of Arles, promoted monastic life. Saint John Cassian, familiar with monasticism in Egypt and Palestine, founded two monasteries near Marseilles around 415 AD after being ordained a deacon by Saint John Chrysostom in Constantinople.

Through these developments, the role of the Orthodox monk was clearly defined, establishing a legacy that would shape monastic life across generations and geographical boundaries. The balance between community and personal asceticism remains a cornerstone of the Orthodox monastic tradition today.

The Role of Orthodox Monasticism in Byzantine and Ottoman States

The evolution of monasticism during the fourth century significantly influenced the religious landscape of the Byzantine Empire. Many Orthodox monks actively engaged in the defense of the faith, particularly against various heresies, including those related to Christological doctrines. While the majority of monks upheld Orthodox beliefs, Eutyches, an archimandrite from Constantinople, led the monophysite heresy. In contrast, Saint Maximos the Confessor (c. 580-662) played a crucial role in combating monothelitism and monoenergism. The Sixth Ecumenical Council (680) ultimately condemned these heretical views, reaffirming the doctrine established at Chalcedon.

During the iconoclastic controversy, the Studite monks, under the leadership of St. Theodore the Studite (759-826), were instrumental in opposing the iconoclasts. St. Theodore not only organized his monastery, the Studion, according to the cenobitic principles of St. Pachomios and St. Basil but also authored three Antirrhetics against iconoclasm.

Following the condemnation of iconoclasm, monasticism experienced a revival, attracting many members of the Byzantine aristocracy to the monastic life. Monks became key figures in education, with many clergy receiving their training in monasteries. Bishops, metropolitans, and patriarchs frequently emerged from monastic backgrounds, leading to their involvement in church affairs, sometimes benefiting the church, while at other times creating challenges. Monasteries were established in nearly every diocese, with the bishop serving as their overseer. Since 879, the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople has had the authority to bless monasteries under the jurisdiction of other dioceses, leading to the establishment of “Patriarchal Stavropighiac Monasteries,” a tradition that continues today.

The Arab conquests of the 7th century prompted the search for new monastic centers, resulting in the establishment of significant sites such as Mount Olympus in Bithynia and the Holy Mountain of Athos.

Throughout the Byzantine era, Orthodox monks played an active role in church life, drawing strength from their spiritual practices. Two main schools of thought emerged regarding Christian anthropology: one influenced by Evagrios Ponticus (d. 399), which emphasized a dualistic view that de-emphasized the body, and the other represented by St. Makarios of Egypt, which embraced a more holistic view of humanity as a psycho-physical entity destined for deification. In this context, “prayer of the mind” in Evagrian spirituality evolved into the “prayer of the heart” in the Macarian tradition, with both perspectives continuing to find adherents in the church’s history.

Saint Symeon the New Theologian (949-1022) marked a significant development in monastic spirituality. Initially a disciple of a Studite monk, he later became the abbot of the small monastery of St. Mamas in Constantinople. His works, including the fifty-eight hymns of “Divine Love,” emphasize that Christian faith is a conscious experience of God. St. Symeon advocated for an intensive sacramental life that fosters a personal experience of God, paving the way for Hesychasm, which emphasizes this personal encounter alongside sacramental participation.

The spirituality of Hesychasm, articulated in the theology of St. Gregory Palamas (1296-1359), became crucial not only for monastic life but also for the broader church. As an Anthonite monk, St. Gregory defended the Hesychasts of the Holy Mountain against criticisms from Barlaam the Calabrian, who accused them of materialism. The Hesychastic prayer method is repeating the “Jesus Prayer” aloud while synchronizing one’s breathing: “O Lord, Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.” This practice aims to bring the prayer from the lips and mind into the heart, culminating in a profound peace and the experience of divine light.

Saint Gregory affirmed the authenticity of the Hesychasts’ experiences, likening them to the disciples’ encounter with Christ on Mount Tabor. Theologically, he explained this experience through the distinction between God’s essence and energies, affirming that the “uncreated light” they encountered was an authentic manifestation of God’s presence.

After the fall of Constantinople, the number of idiorrhythmic monasteries increased, leading to a decline in organized monastic life. The 16th century represented a low point for monasticism. In response, many monks on the Holy Mountain shifted towards idiorrhythmic lifestyles, establishing dependencies of main monasteries with stricter observances. Patriarchs such as Jeremy II of Constantinople and Sophronios of Jerusalem worked to counter the spread of idiorrhythmic practices. While cenobitic monasticism prevailed for a time, idiorrhythmic tendencies soon resurfaced, with many significant monasteries on the Holy Mountain adopting this model. Presently, while an idiorrhythmic monastery can transition to cenobitic, the reverse is not permitted, a structure intended to preserve the organized monastic life based on the ideals established by Saint Basil.

Monasticism also played a vital role during the Ottoman Empire, as Orthodox monks preserved both the faith and Greek culture. Monasteries continued to serve as educational centers for clergy and became clandestine schools (Krypho Scholeio) for the Greek population under Turkish rule. Monks became natural leaders in the resistance against oppression, exemplified by the Greek Revolution, which began in 1821 at the monastery of Aghia Lavra, where Metropolitan Germanos of Old Patras raised the banner of revolution.

The Holy Mount Athos Monastic Community

Monasticism on Holy Mount Athos has roots that predate the tenth century. During this time, many anchorites resided in the region, particularly around Ierissos. These solitary monks, known as Orthodox monks, lived in cells (kellia) and organized themselves by selecting a leader, or “protos,” to maintain a semblance of order. Some of these cells housed multiple anchorites and were collectively referred to as “monasteries.” Notably, two monasteries existed on the mountain before the tenth century: Zogrophou and Xeropotamou.

The establishment of cenobitic monasticism, which laid the groundwork for the Great Republic of Monks on Mount Athos, began in 963 with the construction of the cenobitic monastery of Meghisti Lavra by Athanasios the Athonite. He received support from Emperor Nicephoros Phokas and continued backing from Emperor John Tsimiskis. This monastery quickly became a “pan-Orthodox” community, welcoming monks from diverse backgrounds, including Iberians (Georgians), Russians, Serbians, Bulgarians, and Romanians, alongside Greeks.

Each monastery was led by its own abbot, while the “Protos,” a chosen leader, was appointed directly by the emperor. Following the model of the Lavra, which enjoyed autonomous status, all monasteries were classified as royal monasteries, operating without ecclesiastical oversight. However, this changed during the reign of Emperor Alexios Comnenos (1081-1118), who granted the Patriarch authority to supervise the monasteries through Novella 37, transforming them into “Stavropighiac” and Patriarchal entities. The Patriarch appointed the Bishop of Ierissos to represent him on Mount Athos.

The rise of idiorrhythmic monasteries under Ottoman rule had a significant impact on the Holy Mountain during the seventeenth century. Many monasteries dismissed their abbots and the Protos, leading to the replacement of abbots with a group of trustees elected annually by the monks. The Protos was succeeded by four supervisors (Epistatai) who rotated each year, with one designated as the chief supervisor (Protepistatis), serving as “first among equals.” Today, the Republic of Monks, comprising twenty monasteries, continues to convene a Synaxis with representatives who meet twice a year or as needed. The representative from Lavra presides over these gatherings. This governance structure, established in 1783 by Patriarch Gabriel IV of Constantinople, still regulates life within the Athonite monastic community.

Orthodox Monasticism Today

The spread of monasticism to Slavic countries occurred with the conversion of the Slavs in the ninth and tenth centuries, and it continues to flourish despite historical challenges, including communist oppression. Notable monasteries in Russia, such as Zagorsk, Optino, and Valamo, uphold the hesychastic tradition. Esteemed monks and spiritual figures, including St. Nilus (1433-1508), St. Seraphim of Sarov (1759-1833), and Father John of Kronstadt (1829-1908), have been prominent in this tradition. In Bulgaria, Serbia, and Romania, monastic life is still very much alive.

On Holy Mount Athos, a remarkable monastic renewal is currently underway. Several previously inactive monasteries have been revitalized by young, educated, and enthusiastic Orthodox monks, infusing new life and spirituality into the community in line with the teachings of St. Basil. For instance, the monastery of Stavronikita has benefited from this resurgence. Under the guidance of influential spiritual fathers like Father Ephraim (abbot of Philotheou), Father Aimilianos (abbot of Simonos Petra), and Abbot Vassilios (of Stavronikita), monastic life is thriving both spiritually and intellectually. The pattern of cenobitic living is re-emerging and gaining momentum.

Furthermore, spiritual fathers from Mount Athos have been visiting the United States, fostering interest among young men and women eager to embrace monastic life and promote its traditions in America. The St. Gregory Palamas Monastery in Hayesville, Ohio, under the Greek Orthodox Metropolis of Pittsburgh, exemplifies this potential for growth.

Today, a monastic renewal is occurring across many Orthodox countries as a response to the materialistic trends in society. Monasteries such as Longovarda Monastery in Nea Makri and St. John’s Monastery on Patmos are active examples in Greece outside of Mount Athos. The Synodal Church Outside Russia is in charge of important shrines, monasteries, and Holy Places in the United States.

For more information about monasteries in the United States, you can explore the following resources:

- The Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America’s monasteries

- Male Monastic Communities (Assembly of Canonical Orthodox Bishops of the United States of America)

- (Assembly of Canonical Orthodox Bishops of the United States of America) Female Monastic Communities

Differences Between the Life of a Bishop and an Orthodox Monk

The life of a bishop and that of a simple Orthodox monk share common spiritual foundations, yet they diverge significantly in responsibilities and roles within the Church. The archpastoral ministry is a form of obedience that requires an ascetic lifestyle and deep focus on cultivating the grace of the Holy Spirit. This commitment can be seen as akin to simple monasticism but often demands even greater levels of dedication due to the substantial responsibilities a bishop bears.

Bishops are held to all the monastic vows that apply to Orthodox monks, but they also shoulder an additional burden: the profound responsibility to God and the Church. They are viewed as shepherds and spiritual leaders by their congregations, tasked with upholding the faith and guiding their communities.

Guidance for Those Considering Monasticism

For individuals contemplating a monastic life, it’s crucial to approach this decision with serious reflection. An earnest desire and conviction about one’s vocation are essential, typically after a period of testing one’s commitment. Many young people find themselves “at a crossroads,” often expressing uncertainty about their calling to monasticism. In such cases, I advise that if there remains even a hint of doubt, one should refrain from taking monastic vows.

Rushing into this life can lead to significant spiritual and personal challenges. It’s often more prudent to wait at least three years to determine if one’s initial enthusiasm endures. Making a hasty decision can have dire consequences, as breaking monastic vows can leave individuals with deep spiritual wounds, making it difficult to return to a normal life.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the lives of bishops and Orthodox monks are both dedicated to spiritual growth and service, yet they encompass distinct roles and responsibilities within the Church. Bishops carry the weight of leadership and the duty to guide their communities, while monks focus on personal asceticism and communal life. For those contemplating a monastic vocation, careful reflection and discernment are essential. It is crucial to ensure a genuine calling before committing to this profound path, as the decision to take monastic vows can have lasting spiritual implications. Ultimately, both paths contribute to the rich tapestry of Orthodox Monk Christian life, each fulfilling unique purposes in the pursuit of holiness and the service of God.

FAQs About Orthodox Monastic Life

1. What is the primary role of an Orthodox monk?

An Orthodox monk dedicates their life to spiritual growth, prayer, and communal living, focusing on achieving a closer relationship with God through ascetic practices and a life of simplicity.

2. How does the life of a bishop differ from that of an Orthodox monk?

While both bishops and monks commit to spiritual development, bishops bear the added responsibility of leading and guiding their congregations, whereas monks focus primarily on their personal spiritual journey and community life.

3. What are the main vows taken by an Orthodox monk?

Orthodox monks typically take vows of chastity, poverty, and obedience. These vows reflect their commitment to a life of devotion and service to God.

4. How should someone prepare for a monastic life?

Individuals considering monastic life should engage in serious reflection, seek spiritual guidance, and spend time in prayer. It’s advisable to test their commitment over a period of time before making any vows.

5. Can someone leave monastic life after taking vows?

While it is possible to leave monastic life, doing so can have significant spiritual and emotional consequences. Breaking vows may result in spiritual wounds, making it challenging to return to a regular life.

For Getting More Information Thezvideo.